|

Smith—aviation mechanic, Army Veteran, and past commander of the American Legion post in Gridley, California—died suddenly after a surgical procedure at age 52. His brothers and young son had the body cremated at the new crematorium at what is now Los Angeles National Cemetery. Afterward, his ashes were placed in the nearby indoor columbarium, Bay 300, Row A, “Cinerarium” 1—the first interment. Cremation was a practical choice for Smith’s family and their decision reflected the move away from casket burials on the West Coast at this time. In the United States, cremation of the dead and interment of the ashes or cremains in above-ground structures known as columbaria grew increasingly popular in the 1920s. Before contagious disease was fully understood, cremation was touted as a sanitary way to dispose of bodies—and perhaps a necessity in a pandemic. By the time scientific advances in the 1930s disproved this idea, many Americans viewed cremation as an appealing burial option. This was particularly true in California, where one-third of all U.S. crematories were in operation. Environmentally practical and architecturally stylish columbaria became a common asset in the state’s cemeteries. Floor plan of indoor columbarium at Los Angeles National Cemetery, c. 1940. The diagram helped visitors locate the niche holding the cremated remains of their loved one. (NCA) At the Los Angeles Veterans cemetery, which opened in 1889 on the grounds of the Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, the graves of Veterans who served from the Civil War through World War I filled much of the acreage. With space at a premium and cremations on the rise, VA built an indoor columbarium and chapel-crematorium in 1940-1941. The Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal-era agency that carried out public works projects, provided the money and the manpower for their construction. The WPA completed other improvement projects at the cemetery, landscaping the grounds, resetting headstones, and building a rostrum. The arc-shaped columbarium, with a covered arcade or “cloister” on the front, was strategically placed midway down the cemetery’s greensward as a backdrop to the low brick rostrum. Inspired by California’s historic eighteenth-century Catholic missions, the structure incorporated “second-hand brick” with “squeezed joints,” terra cotta roof tiles, and stucco. The use of clear, insulating hollow glass block in the windows added a forward-looking material. First introduced to consumers in 1933 at the Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition, glass block gained favor through the decade. Los Angeles columbarium built by the Works Progress Administration, which provided employment for millions of Americans during the Great Depression. (NCA) Inside the columbarium, a central vestibule connects two wings lined with two-dozen bays. Each bay has three walls filled with niches, twelve rows from floor to ceiling that are unmistakably reminiscent of post office boxes. The niche covers are made of an early metal alloy. Skylights and clerestory windows draw in natural light to create a pleasant setting “to visit the dead,” a stark distinction from previous generations of dark, somber columbaria. The plans for the Los Angeles columbarium included a matching structure to the east, which would have created a symmetrical focal point in the cemetery, but the second structure was never realized. The nondenominational chapel erected by the WPA at the cemetery’s entrance provided related functions such as viewing rooms and the crematorium. The small number of chapels proposed or built at national cemeteries after World War II were short-lived. By the late 1970s, the Los Angeles chapel was used for administrative and committal-service functions, and the crematorium equipment had been removed. Decades after Private Smith was inurned at Los Angeles and shortly after VA assumed responsibility for the national cemetery system in 1974, the agency made outdoor columbaria a requirement at all new cemeteries. The first was completed at Riverside National Cemetery in California. By the early 1980s, they were also being built at existing cemeteries in locations unsuitable for caskets, such as hillsides and along perimeter walls. VA cremation burials had reached 9 percent, and the addition of columbaria enabled older closed cemeteries to reopen. The future of Los Angeles National Cemetery, where available gravesites were generally depleted by 1976, has been revived with an all-columbaria tract opened in 2019 that eventually will accommodate 90,000 cremains. The need for such facilities is greater than ever, as cremation interments accounted for over 55 percent of all VA burials in 2021, just under the national rate. Meanwhile, VA is investing in its historic columbarium with a comprehensive rehabilitation project that will include a new tile roof, repairs to structural components and windows, and interior finishes. This unique building illuminates the shift in burial practices that occurred between the world wars and, like so many trends, it started in California. Reprinted with permission from the National Cemetery Administration historian of the National VA History Center. Object 48 is part of the History of VA in 100 Objects exhibit and expands on the first columbarium built on a national cemetery property. Other memorial objects from the exhibit include:

If you like this article and would like to learn more about the history of cremation and how it relates to modern cremation, check out Cremation Then & Now, a production of Undertaking: The Podcast, wherever you listen to podcasts. Cremation Then & Now is hosted by Barbara Kemmis, Executive Director of the Cremation Association of North America (CANA), and Jason Ryan Engler, CANA Historian. Find episode 408 for more on Cremation Societies and Memorialization. To provide some sort of structure, cremation’s earliest supporters often aligned themselves in Societies and Associations – which were fueled by the reformation of burial practices. Upon payment of their dues to their society or association, members were not only supporting the building of a crematory in their community, but they were also prepaying for their own cremation. Their membership also made them part of an important social group – meetings were often like those of other social and fraternal organizations – the only difference was that cremation was their theme.  A particularly important method for early cremationists to get their message out was by publishing what has since been referred to as propaganda. Cremation societies frequently published various booklets and pamphlets which featured reasoning for choosing cremation over burial, locations of the crematories in the US, opinions of notable persons who supported the movement, and photos of the “crematory vaults” and urn selections. A cremation society in France created propaganda that included photos of bodies in various states of decomposition after burial. Many US crematories circulated this same literature, theirs showing the gruesome images along with photos of their beautiful crematories and columbaria on the facing page. Additionally, in the late 1800s, three societies published magazines for their members – The Urn (published by the U.S. Cremation Company in New York), Modern Crematist (by the Lancaster Cremation and Funeral Reform Association in Lancaster, Penn.), and The Columbarium (by the Philadelphia Cremation Society), all of which ceased publication by the end of the century. Poets and modern thinkers of the day often added their notes of support as well. For instance, the poet Arlo Bates lent his support of cremation when he wrote: Let me not linger in the tainted earth, to fester in corruption’s shroud of shame, But soar at once, as through a glorious birth clad in a spotless robe of cleansing flame. Then wrap about my frame a robe of fire and let it rise as incense censer swung; until in ether pure, it may aspire to greet the stars along the azure flung. And let me rise into a filmy cloud and touch with gold the amber sunset sky; or veiled in mist the driving storm enshroud both land and tossing main – as on I fly. Women’s suffrage supporter Frances Willard was also an ardent supporter of cremation. She stated: “I choose the luminous path of light rather than the dark slow road of the valley of the shadow of death. Holding these opinions, I have the purpose to help forward progressive movements even in my latest hours, and hence hereby decree that the earthly mantle which I shall drop ere long – shall be swiftly enfolded in flames and rendered powerless to harmfully effect the health of the living.” THE CREMATION ASSOCIATION OF NORTH AMERICAEarly on, cremationists and cemeteries who conducted cremations often struggled due to a lack of some sort of guidance and direction. There was no infrastructure or national organization to give this direction as there was in Europe where many of the crematories were operated by state and local municipalities. Dr. Hugo Erichsen, a physician in Detroit, Michigan, and founder of the cremation society there, changed that when, in early 1913, he issued an invitation to all American cremation groups to join and form a society with a national scope. He was successful in bringing 14 delegates of the 50 or so crematories in operation together under one roof and the Cremation Association of America was born. While Dr. Erichsen’s initial goal was burial reform, and for the first several years his focus was realized, the Cremation Association quickly developed into meetings of the businessmen who performed cremations in their communities – largely because the reform societies which built many of the early crematories in the country were taken over by them. The Association still thrives today and is unequivocally the source for cremation education, statistics, and information. The name was changed in 1975 to the Cremation Association of North America to reflect member involvement from crematories across the continent. CREMATION IN TRANSITIONThe modern Cremation movement in America sprang from a sanitary necessity; but over time the embalming process evolved into more common practice. This disinfection of the body, along with the advent of medicine into everyday life, the need for cremation as a means of purification after death dwindled. With sanitary concerns negated, the primary argument in favor of cremation was invalidated. New reasons to choose fire over earth needed to be enumerated, and with them, a new era in the history of cremation in America began.

Ten years and four months ago I decided the next step in my career was to become an executive director. I started looking at job postings and stumbled across one for the Cremation Association of North America. My first reaction was to chuckle and marvel that there really is an association (or three) for any profession. I applied for the position, bombed the phone interview, aced the in-person interview and the rest is history. Too often, we talk about how slow this profession is to advance. Looking back, however, it’s been an exciting decade of change and growth for the industry and our association in particular. In 2011, CANA was 98 years young – a startup transitioning from an association management company to hiring their first association professional to take the organization to the next level. Cremation was still a threat rather than a reality for non-members. In 2021, cremation is the new tradition and other forms of disposition are clamoring for their own place. CANA’s staff is some of the most dedicated in the business, continuing to evolve our offerings to meet the needs of members and the entire profession. I can see how much I have learned and continue to learn. Here are ten reflections on cremation and CANA in 2021 compared to 2011: 1.) Cremation is MainstreamIn 2011, CANA was the primary cremation education provider and I was routinely told by well-known thought leaders that cremation was irrelevant and a fad. Others were angry about the growing adoption of cremation and accused CANA of destroying their businesses. Cremation was still considered to be a fringe disposition to be feared or ignored. “Cremation is taking food out of my children’s mouths!” expressed a tipsy monument dealer at one of my first professional meetings in fall 2011. I didn’t take this personally at the time, and he later apologized, but I soon learned that cremation had a greater negative impact on cemeteries and memorial suppliers than other types of businesses. That impact continues, but even then, there were opportunities going unexplored. If cremation is the opposite of casketed burial, as consumers seem to understand it, then traditions linked to burial are often viewed as disconnected to cremation. Why then were cemeteries largely offering burial for cremated remains as the only permanent placement option? Why were the companies building and selling monuments and mausoleums avoiding building columbaria? When I asked these questions early on in my career, I heard variations on the theme that these are business decisions. Now it is clear that cremation is a persistent trend and all types of CANA members are aware of that and eager to explore how it can grow their businesses. Today’s business decisions incorporate cremation in planning and product development. Those previous era’s thought leaders are largely retired or have changed their tune. We have all learned a lot. 2.) Cana's Brand is more than crematory operations“I don’t own or operate a crematory, so I don’t belong to CANA,” was the common response I received when pitching CANA membership. And it was true, CANA was and is the market leader in crematory operations training and expertise. I learned how to answer questions posed by members and regulators alike. Funeral directors were fielding questions from families choosing cremation and needed to learn more about the technical process to respond with accurate and valuable information. Membership has tripled over the past decade and the growth is among businesses without crematories. They join CANA to learn how to increase profitability and learn strategies to better serve grieving families beyond the basic (though all-important) crematory operations. 3.) CREMATION ADOPTION IS 100% CONSUMER DRIVENSince 2011, the cremation rate has grown from 63.1% to 73.1% in Canada and from 42.2% to more than 56.1% in the U.S. — almost a 15% increase. I wish that the five CANA staff members and I could claim that we move the cremation rate forward. That would be a remarkable accomplishment. Rather we, like you, are focused on keeping up with and reporting consumer preferences and trends. The more we understand, the better we can bridge the growing disconnect and mistrust between death care professionals and the public. I am proud that we have created a website with cremation memorialization material that helps consumers make decisions and is so valued. 4.) CANA RESEARCH IS THE MOST ACCURATE AND RELIABLE OUT THERE Research is my favorite part of the job. I am a librarian by training and I love helping CANA members find information that helps them. But when I am asked the same question more than a few times, I see a research opportunity. CANA is best known for its rock-solid cremation trend analysis and projections. Building on that reputation, we are expanding into more consumer research with our recent Cremation Insights report and some exciting projects planned for the coming years. 5.) CANA, THE MEMBERSHIP ASSOCIATION, IS STRONGER THAN EVERIn the macro world of professional and trade associations, membership is decreasing (as is attendance at conventions). With social media and “free” information online, more people are choosing not to affiliate with an association, but seek connections elsewhere. CANA bucks these trends with a +95% member retention rate and attracting more than 100 new members a year. Fundamentally, associations reflect their member’s challenges and successes. Associations must change and adapt to meet these needs. For example, CANA responded to the growing adoption of online education by creating an online version of its Crematory Operations Certification Program (COCP) in 2017. By 2019, more operators were certified online than in person for convenience and accessibility reasons, but all received the same training and content. I am grateful that CANA’s education offerings are diversified. Building on that success, we offer CE courses, webinars, and professional development online – we’re investing to make CANA Education available anywhere. Trends like consolidation, business closure and briefer attention spans are real challenges for all associations that CANA addresses head on. 6.) BOTH/AND IS OUR NEW REALITYThis term may be unfamiliar to you, but “both/and” is the concept that when new technologies or products come along, you must add those to existing offerings without dropping anything. CANA members are definitely facing this challenge. Most continue to serve casketed burial families as well as cremation, but the proportion of each type of death call has likely flipped. Or perhaps the proportion of calls received via a website versus the brick-and-mortar funeral home has reversed. Cemeteries are making significant capital investments in cremation product options, while still supporting casketed burials. And the increased desire for personalization is another layer of creating new traditions for families who are choosing cremation for the first time. 7.) THE CREMATION CONTINUUM HAS SHIFTEDA decade ago, as I was analyzing CANA member records and meeting members, the majority of members had multiple brands. The brand that was primarily cremation-focused was often the business that held the CANA membership. All funeral service providers could support cremation consumers, and many funeral homes had added “& Cremation Services” to their business names. Generally speaking, cremation societies were largely considered to be “bottom feeders” by their traditional, brick-and-mortar competitors. Advertising on price was a newer, controversial concept. Fast forward to a world where many CANA members retain their Funeral Home and Cremation Society, and have added an online brand as well. The goal of this diversification is meeting cremation consumers where they are and offering a variety of options. This trend is true for the national, publicly traded members as well as regional or local providers. Advertising on price is widely accepted and expected for the value brands, whereas the service-oriented brands tend to promote personalization and excellent service. Cremation consumers have more choices in service providers than ever. 8.) THE RACE TO THE BOTTOM PERSISTSThe assumption that cremation consumers choose cremation for the lowest price persists and it is damaging to our profession. Very few businesses can survive, much less thrive, on the volume necessary to support low prices. There are low-cost providers in nearly every market already, but emphasis on market share is crucial. Low income and poor families don’t default to cremation because of price. They crowd source funeral funding for the disposition they want, or, sadly, they abandon their loved one. Indigent deaths are on the rise and that is the result of a complete lack of funding for an unexpected death. Assumptions are creating more distance from the consumer and add to misunderstandings. 9.) Cremation is the new traditionIn May 2019, CANA and Homesteaders Life Company conducted joint research on the cremation experience. This research resulted in 7 key insights, but our first critical lesson was when designing the research. We contracted with focus group research centers to create groups for us divided into Direct Cremation and Cremation with Service groups. We defined Direct Cremation as people who chose cremation and did nothing, conducting no services. The contact called us back and said they had hundreds of potential participants in our focus groups who chose cremation and were willing to talk about their experience, but they couldn’t find any Direct Cremation consumers. The mistake we made was defining Direct Cremation as doing nothing, when we meant doing nothing with a cremation provider. People who choose cremation always do something—the question is whether they view the funeral director as an expert to help them create new traditions, or as a body handler. This is my primary question as I face the next decade. 10.) CREMATION IS PREPARATION FOR MEMORIALIZATIONCANA has believed that for over 100 years and CANA members agree to the Code of Cremation Practice as a condition of membership. Promoting permanent placement, ceremony and all the other aspects that memorialization supports continues to be our challenge and opportunity. That monument dealer, who adjusted his model and is still in business, was correct, in part. We are fighting against consumer resistance to memorialization and permanent placement, but it is a fight worth winning. Ten years ago, I joked that I was the executive director of a 100-year-old start-up, but that is the culture I have attempted to maintain over the past decade. CANA is progressive and committed to creating and delivering content that supports our members and promotes ethical, transformative cremation experiences. I am still learning every day and the staff and I always appreciate your feedback, questions and suggestions. This work is hard and requires imagination, reliable data to make decisions and collaboration. I hope you will join me in raising a glass to my first ten years with CANA and all we have accomplished together! October 17, 2021 was 10-years to the day that Barbara started as Executive Director of CANA. Join the staff and board in celebrating and congratulating Barbara and the whole association on the achievements of the last decade. There's no end to the celebration in October: wish her a Happy Birthday October 24th

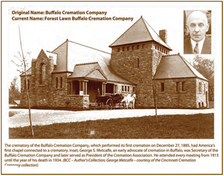

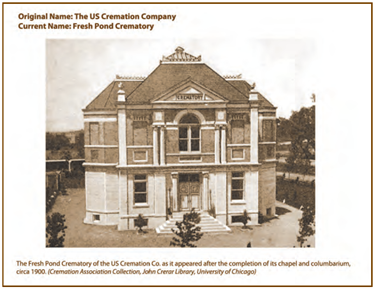

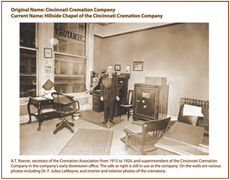

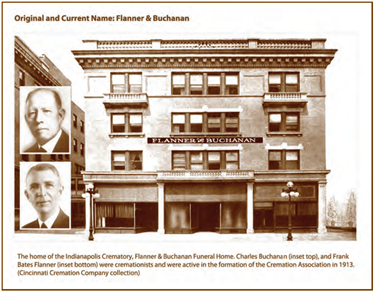

With the opening of The History of Cremation Exhibit at the National Museum of Funeral History (and the holidays making us a bit introspective and nostalgic), we’ve had a renewed sense of interest in the history of the cremation movement—and therefore the history of the Cremation Association. And we thought we’d take the time to celebrate some of the establishments that had representatives at the first convention in Detroit in 1913 remain part of CANA today. (While not all have maintained continuous membership for all of the association’s 105-year existence, their memberships are current now, at a time when cremation education and information are in high demand.) In early 1913, Dr. Hugo Erichsen sent invitations to every crematory in existence, and even to some strong advocates who were not affiliated with crematories. An advertisement in Modern Cemetery Magazine “proposed to establish a national organization and discuss various questions of practical import relating to the best methods of advertising, management of crematoria, etc.” which became CANA. Erichsen’s invitation brought fourteen representatives from ten of the fifty-or-so crematories in operation at the time. Along the way, several established crematories added their names to the roster of the association and they too have given their continued support for cremation. We share seven stories of these earliest delegates, and current CANA members, below. the buffalo cremation companyBUFFALO, NEW YORK  The Buffalo Cremation Company completed its “Crematory Temple” just after its first cremation took place on December 27, 1885. The engineer for the crematory came to the U.S. from Italy to oversee the construction. The temple was unlike any structure built in the U.S. at the time. In fact, it would be a couple more years before a complete cremation facility was completed at the Missouri Crematory at St. Louis. The delegate for the Buffalo Cremation Company was George Metcalfe. Endeared to many and known as “Uncle George,” Metcalfe was in attendance at all but one Cremation Association convention from its inception to his death in 1934. At present, the crematory is still in operation as the Forest Lawn Buffalo Cremation Company under Joseph Dispenza and his capable staff. the us cremation companyMIDDLE VILLAGE, NEW YORK  The US Cremation Company completed their more utilitarian structure housing only the cremation apparatus, and conducted their first cremation on December 4, 1885. Their membership in the association came after the first meeting, their delegate, William Berendsohn, serving as our third president from 1918-1920. The crematory is now operated as the Fresh Pond Crematory and is managed by memorialization advocate Joseph Di Troia, a second-generation operator. THE CINCINNATI CREMATION COMPANYCINCINNATI, OHIO  After the US Cremation Company and the Buffalo Cremation Company, the Cincinnati Cremation Company operates the third-oldest operating crematory in our country. The cremation furnace was completed and their first cremation took place June 22, 1887. Their chapel was added in 1888. Additionally, they sent a delegate to the first meeting of the Cremation Association, A.T. Roever, and, in 1915, he was elected Secretary – a post he held for almost a decade. Later, R. Herbert Heil operated the Cincinnati Cremation Company, and served as president of the Cremation Association from 1947-1949. Today, the Catchen family own and operate the crematory and columbarium as the Hillside Chapel of the Cincinnati Cremation Company. CREMATORIUM, LIMITEDOUTREMONT, QUÉBEC In Canada, the first crematory in operation was the Crematorium, Limited, operated on the grounds of the Mount Royal Cemetery in Montreal, Quebec. Construction on the crematory here was begun in 1900, and it completed its first cremation in 1901. Their delegate to the first Cremation Association meeting was W. Ormiston Roy, who was the first to confirm his attendance after Dr. Erichsen’s invitation to the 1913 meeting in Detroit. He served as our president from 1920-1922. Mount Royal Cemetery has now assumed control of Crematorium, Inc.’s operations, and it is still a sought-after and popular cremation services provider. FLANNER & BUCHANANINDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA  In 1904, the leading Indianapolis undertaking firm Flanner & Buchanan decided their establishment was incomplete without the appropriate facilities for serving families who desired cremation. The nearest crematories were more than 100 miles away, and at least one of the active members of their ownership, Charles Buchanan, was a cremationist. At the time, their firm was one of just a handful of funeral directors that owned a crematory. They became active in the Cremation Association, Charles Buchanan being present at the first meeting, then serving as president from 1922-1925. Additionally, Frank Bates Flanner, while not an officer of the Cremation Association, made many presentations at conventions and wrote many informational pamphlets for better relations between funeral directors and crematories, which had been an antagonistic relationship even in those early days. While the original building and even the second building have long been razed, Flanner Buchanan is still thriving as a leading funeral services provider in Indianapolis and surrounding areas. FRESNO CREMATORYFRESNO, CALIFORNIA  Fresno’s Chapel of the Light, established in 1914 as the Fresno Crematory, was begun by a reform society of cremationists in their city. After struggling with their ability to successfully operate a crematory, the trustees of the crematory approached Lawrence Moore, operator of the California Crematorium in Oakland, to take over their operations. He purchased a majority of the stock and became the owner in 1919. On what was to be a brief assignment, Moore sent one of his employees, Herbert Hargrave, to operate the facility. He ended up staying in Fresno and quickly became involved in the Cremation Association. In 1925, he was elected Secretary and maintained that position until his retirement in 1979, with the exception of a two-year term as president from 1935-1937. He operated the Chapel of the Light from his initial assignment there until his death in 1981. Herbert Hargrave’s son, Keith, worked with his father at the Chapel of the Light, serving his Cremation Association presidency from 1985-1986. He became involved in the crematory’s operations in 1955, assuming management responsibilities at his father’s retirement. He served as General Manager throughout acquisitions and the selling of the firm and was a mainstay in the company until his death in 2014. VALHALLA CREMATORYST. LOUIS, MISSOURI The second crematory constructed in St. Louis was completed in 1919 by the St. Louis Mausoleum and Crematory Company, a division of the National Securities Company in St. Louis, and on the grounds of the Valhalla Cemetery on St. Charles Rock Road. Their involvement in the Cremation Association was begun by Robert J. Guthrie, who served as treasurer of the Association from 1925-1932 when he was elected president. Just two years later his death ushered in a new branch of his family. Having no children of his own, Guthrie left the operations of the Valhalla Chapel to his niece’s husband, Mr. Clifford F. Zell, Sr. The Zell family have been some of the most influential cremationists in American history. Their facility in St. Louis was a blending of the east and west coast ideas of cremation and inurnment. In addition to Mr. Guthrie, their family produced three past-presidents of the Cremation Association, Cliff Zell, Sr., Cliff Zell, Jr., and the first-ever female president of any funeral service or cemetery organization, Genevieve “Jinger” Zell, wife of Cliff Zell, Jr. Valhalla is still under the operation of the Zell family. It would take pages upon pages to list the crematories in the country and their respective individuals that have been active in our Association since our beginning in 1913. Suffice it to say that all have served in countless capacities—from leading the association as officers and board members to faithfully paying dues each year—and each have contributed in their own ways to the growth and success of our association and of the cremation movement in North America. Past, present, and future, our association’s membership continues to be the guiding force of cremation in America. This post is excerpted from an article of the same name originally published in The Cremationist Volume 52, Issue 1. Since then, we’ve celebrated our 100th Convention, our 105th Anniversary, and the opening of the first History of Cremation Exhibit at the National Museum of Funeral History. It’s been a busy two years and we’re grateful for the continued leadership and support of our members both old and new. Thank you for all you do for the association, the profession, and your communities – it just wouldn’t be the same without you.

Happy Holidays from CANA. How to Donate to the History of Cremation Exhibit Financial or artifact contributions are what make the History of Cremation Exhibit possible. Please consider donating to the History of Cremation Exhibit today.

The funeral industry has a challenge on its hands: consumers are choosing cremation, but they know little about it. They don’t know the process, the possibilities for memorialization, and they don’t understand cremation’s history. Worse, because America’s cremation story has largely been untold, misconceptions about the industry fill the gaps. Cremation in the United States is the new tradition. In 2016, cremation reached a major milestone when it eclipsed casketed burial as the most popular form of disposition—and it shows no signs of slowing. In 1960, only 3.6% of Americans chose cremation. In 2016, 50.1% did. But even as cremation has soared in popularity, a significant lack of understanding about the process and possibilities of cremation exists. That’s why the History of Cremation Exhibit is so important. On September 16, the National Museum of Funeral History (NMFH) celebrates the opening of The History of Cremation Exhibit, a joint project developed with CANA to tell the full-circle story of cremation in America: from chronicling its birth in Pennsylvania to demonstrating a step-by-step modern cremation process and illuminating the seemingly endless possibilities for memorialization. Visitors will walk away with a new respect and appreciation for this widely misunderstood industry. WHAT DOES CREMATION HAVE TO DO WITH FUNERAL HISTORY?The National Museum of Funeral History was founded in 1992 to realize Robert L. Waltrip’s 25-year dream of establishing an institution to educate the public and preserve the heritage of death care. The Museum provides a place to collect and preserve the history of the industry, including how it began and how it has evolved over time. Permanent exhibits feature vintage hearses, international funerary practices, and tributes to notable figures, but no exhibit had touched on the fastest growing method of disposition in the Western world – cremation. Like its history in America, the global story of cremation is marked by wide-swinging societal shifts. From its ancient use in Roman and Greek culture to purify and honor souls through fire, to its Christian condemnation as a pagan ritual, cremation’s road has been long and conflicted. And people were curious about this story – museum visitors left comments about cremation’s glaring absence from the museum when it’s so present in society. HOW DID CREMATION MAKE SUCH A GIANT LEAP FORWARD IN AMERICAN SOCIETY?: THE FIRST US CREMATION (AN EXHIBIT SNEAK-PEEK!) In 1876, the LeMoyne Crematory in Pennsylvania became the first crematory in the United States. That same year, a man named Baron De Palm was the first person cremated there. The inaugural cremation was an event. Local Board of Health members and physicians were invited. Crowds gathered outside the crematory hoping to get a glimpse of the mystical method of disposition by fire. A handful of honored guests received a small, clear apothecary jar filled with a portion of De Palm’s cremated remains. Those jars signify the birth of cremation in America, and one of them will be on display at the unveiling. Visitors will experience the transition from 1876 to today, from a replica of the LeMoyne Crematory to a modern cremation chamber. The exhibit is a first-of-its kind undertaking, not merely displaying interesting artifacts, but telling a visual story of cremation in America through historical urns, pamphlets, replicas of original equipment and other artifacts, while educating on the technology and memorialization possibilities of modern cremation. Like the witnesses to Baron de Palm’s cremation, the exhibition will allow people to go behind the scenes—seeing cremation containers, the process, how we recycle, and how we memorialize. DEMYSTIFYING CREMATIONMore than getting America’s cremation story in one place, The History of Cremation Exhibit delivers well-deserved clarity to an industry shrouded in mystery. The exhibit will demystify cremation for the public, particularly that cremation memorialization means more than an urn on a mantle. The exhibit will showcase cremation history, but also help the public understand memorialization options and open their eyes to things they never knew about cremation. While cremation continues to rise in the United States—more than half of Americans are choosing it—too often, people stop at “just cremate me.” Moving beyond direct disposal, the exhibit will showcase meaningful ways to memoralize whether adhering to tradition or creating a personalized experience. This exhibit provides an understanding of the complete cremation process, including the role of the funeral director and cemeterian when exploring options for cremation and permanent placement of their cremated remains. BY THE INDUSTRY, FOR THE INDUSTRYThe idea for an exhibit began long ago when Jason Engler, a funeral director who has been involved in funeral service for most of his life, began collecting facts and artifacts at 12 years old. When he joined CANA as its official historian, he began exploring ways to communicate the fascinating beginning of the American Cremation Movement to a wider audience. This exhibit features much of Engler’s own extensive collection as well as other CANA members’ donated time, resources, and artifacts. Together, they tell the story of cremation and the possibilities for memorialization. But it’s not simply about educating the public. The exhibit will demystify cremation for funeral service professionals as well. Even seasoned funeral directors and cemeterians struggle with presenting all the options and effectively educating consumers on cremation. Some in the industry may even personally dislike cremation, but they are not alone. Twenty-first century funeral service professionals are the latest in a long line of professionals who struggled with and succeeded in meeting the needs of cremation families. For a long time, cremation was taboo and certain religions and people within the funeral industry didn’t accept it. But the cremation rate shows that opinions have changed and this exhibit takes a large step toward acknowledging cremation’s history in our profession—and we should take a great deal of pride in it. Understanding the historical context of cremation allows you to learn from the past and embrace the future. WHAT TO EXPECT AT THE HISTORY OF CREMATION EXHIBITA driving force behind The History of Cremation Exhibit is Jason Engler, CANA’s official historian. Engler donated approximately 90 percent of his personal collection of historical cremation items to the exhibit, including:

Throughout the exhibit, visitors will see how cremation has evolved over time—the changes in societal views, equipment, and memorialization options. New in 2022! If you don't have a trip to Houston planned, you can visit the National Museum of Funeral History virtually! The History of Cremation and the 14 other permanent exhibits can be experienced from wherever you are from your device (including your VR headset). For less than $15, you can immerse yourself in cremation history and artifacts, plus you'll see hearses through history, caskets and coffins, and the funerals of US Presidents. Discover a world of historical and international mourning rituals from the comfort of your home with the 360º Virtual Tour! How to Donate to the History of Cremation Exhibit

Financial or artifact contributions are what make the History of Cremation Exhibit possible. Please consider donating to the History of Cremation Exhibit today.

Jason will present on the history of cremation and our association at CANA’s 100th Annual Cremation Innovation Convention tomorrow! Do you know what cremation innovation will look like in 100 years? Share it with us for our time capsule to be opened in 2118! It is impossible to pinpoint a single reason that the rite of cremation gained any acceptance during its early years in America. It was not a popular option and tradition ruled out crematories in many areas of the country. Several of the early crematories were built on a grand and beautiful scale, and this might have influenced public attitudes. However, with only the most basic research, one could easily attribute cremation’s growth to an idea that gripped all areas of death care: the “Memorial Idea.” the memorial ideaThe Memorial Idea began in the cemetery. The establishment of a memorial identity for each person who lived and died was the most important part of the rite of passage called death. Cremationists quickly adopted the idea to include cremation, but the obstacles they faced were harder to overcome than those of their cemeterian counterparts. Clifford Zell, Sr., owner of the Valhalla Chapel of Memories in St. Louis, was the originator of the slogan of the Cremation Association of America (CANA’s original name), a variation of which is still the mantra of our association today. It was during the 1933 convention that Clifford Zell made the statement: “There is one thought I hope that I can impress most deeply on all crematory men – cremation is not the end – cremation alone is not complete, but is only an intermediate step towards the permanent preservation of the cremated remains.” The Memorial Idea stated simply that no cremation was complete without inurnment, which always included ALL of the following:

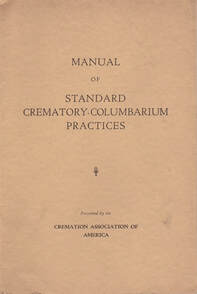

For many years, the urn memorial was so important to cremationists that CANA’s logo, as the Cremation Association of America (CAA), featured illustrations of an urn in a niche. 2. The engraving of the memorial urn When a bronze urn was engraved indelibly with a person’s name and dates of birth and death, the urn became part of the memorial. Together with the other urns in a columbarium, they lent their beauty to add to the overall experience of a columbarium. 3. The permanent placement of the memorial urn Just as every person who lives must die, so too should every person who dies have a permanent resting place. Just as the ancients inscribed names on the urns of their loved ones, the ancient Greeks erected Tumuli in memory of their dead, the Egyptians erected the pyramids, the Romans inurned in columbaria, Kings and Queens entombed in Westminster Abbey, so the placement of the urn became the permanent memorial that cremationists required. This was the utmost concern of the cremationists who were active in the Cremation Association. The inurnment of cremated remains was not always a priority for cremationists, but became the sole purpose of the plight of the association beginning in the late 1920s. Scattering cremated remains, permanent destruction of cremated remains, and home retention of cremated remains were all in direct conflict with the Memorial Idea. Often, the practice was equated with desecration and was fervently discouraged. STANDARDIZING CREMATORY AND COLUMBARIUM PRACTICES The conventions of the Cremation Association were breeding grounds to further the Memorial Idea to those who chose cremation. Lawrence Moore, long-time president and operator of the Chapel of the Chimes in California, was the most instrumental character in the cremation world – he coined the word “inurnment,” invented the first electric-powered cremator, and began the practice of including a unique metallic disc used in every cremation to identify cremated remains. He also was the first to suggest using a cardboard temporary urn to encourage the selection of a permanent urn. Throughout the meetings of the Cremation Association, there were frequent discussions about standardizing the practices of crematories across the country. Many ideas were exchanged on how this could be effected to encompass the cremation customs from the east coast to the west coast and the mix of both in the Midwest. A committee was formed and, after much research, in 1941 the Manual of Standard Crematory and Columbarium Practices was adopted. This manual was considered the textbook of the operations of the modern crematory and columbarium, and became the bible by which cremationists promulgated the Memorial Idea. Throughout the manual, sections dealt with all aspects of operating a crematory and columbarium, but the sections that discussed the handling of cremated remains and the permanent placement of memorial urns were the most doctrinal in nature. During the Memorial Idea era of cremation’s history, most cremationists refused to pulverize, crush or grind cremated remains to reduce their consistency to the cremated remains we picture today. It was the belief that the reduction of the remains to the finer consistency was a desecration to the remains and gave the impression of valueless ash. Their stance also enforced the need for a permanent urn and to aide in the prevention of scattering. The Manual of Standard Crematory and Columbarium Practices spelled it out clearly:

This was further supported by the suggestion for reverent handling of the cremated remains: Cremated Remains Should be Carefully Prepared and Handled Reverently Cremated remains are human remains and are deserving of careful and reverent handling. The attitude of the individual toward cremated remains is oft-times represented by the way he handles them, and the attitude of the crematory-columbarium is definitely expressed by the way remains are prepared and handled by its employees… How can we expect a family or interested party to recognize the fact that cremated remains are human remains and are deserving of proper memorialization if, as crematory-columbarium operators we fail to express by action as well as by word and thought that the remains are sacred? The admonition regarding scattering was perhaps the most doctrinal statement of the entire manual, and carried with it the most important ideal for the cremationist’s purpose: Never Scatter Cremated Remains Cremated remains are not a powdery substance, but the human bone fragments of a loved one. They will not blow away… but will remain where strewn... A request to scatter is frequently made with the supposition that it is the kindly thing, least expensive and least trouble for those remaining. In fact it is usually the most difficult and unkindly request that could be made. Certainly the deceased would not have requested it had they realized the possible heartaches that it would cause. There is comfort in being able to place a flower, on occasion, at the last resting place. Scattering makes this impossible. [There will be] no tangible memory where a flower may be placed in memory. When cremated remains are once destroyed, regrets cannot return them… Much of this may seem like heavy cremationist doctrine, but the cremationists were quite successful in their endeavors. This time frame in cremation’s history in America caused some of the most beautiful memorials imaginable to be created, and they remain beautiful to this day. The idea also caused some very successful revenues for the cremationists. The Memorial Idea revealed the heart of the true cremationist in every way. It took cremation from the hands of reform societies and placed it in the gentle care of business men who brought the idea to life. Unfortunately, by the 1970s, a new idea in cremation began to move in. The face of cremation was about to change drastically. what changed?Cremation’s transformation began in the 1960s. Although influenced by many factors, this change was primarily due to a movement toward simplicity. It was in 1963 that Jessica Mitford wrote her satirical expose, The American Way of Death, lambasting all aspects of the allied funeral and memorial professions. Urged by the excitement that her book spawned, businesses formed to advocate for simple direct cremation and provided easy avenues for those preferring minimal services. The Memorial Idea began to lose hold, and, as it did, the Cremation Association of North America (CANA), led by Genevieve “Jinger” Zell, daughter-in-law of Clifford Zell, Sr., mentioned above, did everything possible to maintain the integrity of what CANA viewed was right: the permanent memorialization of cremated remains. National ad campaigns were initiated and the association’s trade magazine began publication in 1965 to disseminate the news and advocacy of the association. The simplification process that cremation underwent was underscored by the general public’s idea of death care practices. However, this movement did not only affect the memorialization side of cremation – all areas were affected. Cremation chambers were manufactured to ship to different locations, where they had been previously constructed on-site. The first modern crematories were constructed in the basements and wings of chapels across the country, but soon were moved from chapels to garages and metal out-buildings. During the transformation, scattering cremated remains became more and more popular. Crematories installed “cremulators” and processors to reduce the consistency of the cremated remains in order to facilitate cremation. Did scattering encourage processing or, as was the fear of Lawrence Moore in the Memorial Idea period, did processing encourage scattering? The answer is unknown. However, it is clear that the two went hand-in-hand during this time. With the focus of cremation changing from disposition and memorialization to cost-conscious simplicity, the cremation urn industry changed as well. While a majority of urns sold during the time of the memorial idea were constructed of fine cast or spun bronze, aluminum and wood now became popular options. Through all the changes that the cremation profession has faced over the years, the constant underlying ability to succeed amidst the challenges of doing business has proved stronger with membership in the Cremation Association of North America. Since its inception, the association has maintained cremation as its theme, and no other professional association has the roots, track record, singular focus, or knowledge that ours does. All of this has been gained by experience and by maintaining the ability to adapt to the needs and desires of those our members serve. What does the future hold for cremationists? That is entirely dependent on the attitude of the cremationist. If we simply measure how far our profession has come in the years since America’s first modern cremation in 1876, and review how CANA has guided this profession for more than a century since its formation in 1913, we will quickly realize that our true potential lies ahead. In reading the proceedings of almost 40-years-worth of annual conventions of the Cremation Association, I have learned some very important lessons that I can use in my daily dealings with families choosing cremation. Paper dissolves, computers crash, but when a name is engraved on a permanent memorial urn made of material that will last, or on a stone marking a place of rest, these permanent, tangible signs provide stepping stones for future generations. May we never lose sight of the ever-present necessity of our association and our calling, and may we never fail to put families and their needs and desires ahead of our own. We must do all that we can do to maintain the heritage of our ever-changing culture. To do so is to fully serve those who call on us in times of need. It is, after all, what our life’s work is all about. This post is the second in our series on the history of cremation in preparation for the opening of The History of Cremation exhibition at the National Museum of Funeral History. Catch up with the first article and the women who contributed to cremation and CANA. Learn more about the exhibit and how you can contribute on the museum’s website. Jason will present on the history of cremation and our association in honor of CANA’s 100th Annual Cremation Innovation Convention this July. Celebrate with us while learning from the experts on where cremation is going and how your business can continue its success. Update! One hundred years of conventions proves that CANA successfully tackles the topic of cremation by continually providing relevant, progressive content. The 2018 convention was no exception. Excerpted from The Cremationist, Vol 49, Issue 3: “Memorialization: The Memorial Idea” and Vol 49, Issue 4: “Simplification: The Cremation Movement Since the 1960s” by CANA Historian Jason Engler in honor of CANA’s Centennial celebrated in 2013. All photos from the Engler Cremation Collection, courtesy of the author.

Nearly every movement in American history has begun with a handful of hearty men guiding the reins of change and progress. The cremation movement in America is no different. In its early years, a strong cast of characters brought cremation from the dark of superstition into the light of knowledge. F. Julius LeMoyne (builder of the first crematory in the U.S.), Henry Steel Olcott (co-founder of the Theosophical Society), and Dr. Hugo Erichsen (Detroit medical practitioner and founder of CANA), among others, all played important roles in the formation of America’s cremation movement. However, if men were at the head of the early movement, then women most certainly helped to determine the direction of the men’s efforts and encouraged the growing public acceptance of cremation customs. Women were at the forefront in turning the cremation movement into a reality in America because they were among the first people to be cremated in the earliest crematories in the country. The third person cremated in a modern crematory in the United States was Jane Pitman (Bragg), wife of Benn Pitman, the stenographer during the trial of President Lincoln’s assassins. In 1885, Peggy Smith was the first person cremated at Buffalo Cremation Co. (now Forest Lawn Cemetery in New York). Barbara Schorr was the first person cremated at Detroit Crematorium in 1887 (now Woodmere-Detroit Crematorium). In 1886, Olive A. Bird was the first person cremated in Southern California Crematory (now Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery), and in 1888, Elizabeth Todd Terry was the first person cremated at Missouri Crematory (now Valhalla’s Hillcrest Abbey Crematory). Suffragist Lucy Stone was the first person cremated at Massachusetts Crematory, in 1893 (now Forest Hills Cemetery). These pioneering women were so ahead of their time that in several cases their bodies had to be stored while crematory construction was completed. women in the cremation movementThough the final disposition choice of these women demonstrated how the notion of cremation had taken hold, the movement still required living champions. Perhaps the most famous of these was Frances Willard. A noted suffragist and feminist, Willard was well known for her progressive stance in many areas, including the cremation movement. She described her thoughts on cremation and her involvement in the movement in a statement that has become one of the most well known in the history of cremation. When asked her opinion, she stated: I choose the luminous path of light rather than the dark slow road of the valley of the shadow of death. Holding these opinions, I have the purpose to help forward progressive movements even in my latest hours, and hence hereby decree that the earthly mantle which I shall drop ere long – shall be swiftly enfolded in flames and rendered powerless to harmfully effect the health of the living. This quotation proved so meaningful to the cremation movement that a plaque bearing these words hangs in nearly every historic columbarium in the country. Willard was cremated in the Chicago Crematory in Graceland Cemetery upon her death in 1898. Her stance was so notorious that, even after Willard’s own death, a satirical obituary for her cat ran in The New York Times, under the title “To Cremate a Cat.” Followers of the cremation movement increased as the century turned. Authors of the time penned essays informing the public about the cremation option. Sheba Hargreaves was among many who produced pamphlets urging cremation and inurnment. She painted cremation as a beautiful process to be supported and embraced by all who truly cared for their dead. women in memorializationDuring the “Memorial Idea” period of cremation’s history, which began in the late 1920s, there was a concerted effort to ensure that cremated remains were memorialized with the same dignity and dedication as full remains. The leading men of the era, including Lawrence Moore (Chapel of the Chimes in Oakland, CA), Herbert Hargrave (Chapel of the Light in Fresno, CA) and Clifford Zell (Valhalla Chapel of Memories in St. Louis, MO), were strongly supported in their activities by their female counterparts—women such as Alta Phillips (Hollywood Columbarium in Hollywood, CA) and Teresina Morgan (Chapel of Memories in Oakland, CA). At the Chapel of the Chimes in Oakland, an entire cadre of women formed the backbone of the staff. They were charged with describing the Memorial Idea for the families who called upon the crematory for service. Moore felt the women could, like no one else, guide families through the daunting process of choosing a permanent memorial. With the dedication of evangelists, men taught other men the ‘gospel of cremation,’ women of cremation were the true apostles of ‘the good news’ of this ‘sanitary and aesthetic method’ and sold this idea to the families they served. Women’s influence brought many of the most beautiful cremation memorials into existence. Well-known architect Julia Morgan redesigned and constructed one of the most stunning columbaria in the country at the Chapel of the Chimes in Oakland in 1928. This famed chapel would ultimately be named after cremationist Frances Willard and incorporate her famous sentiment. Eventually, this golden age of the “Memorial Idea” began to take a new course in the 1960s. Driven by many factors, the change was primarily due to a movement toward simplicity. In 1963, Jessica Mitford wrote her satirical expose The American Way of Death. Propelled by the excitement that Mitford’s book spawned, the idea of simple direct cremation began to take hold. By the late 1970s the memorial idea started to lose its hold on cremation, and, as it did, the Cremation Association of North America did everything possible to maintain the integrity of what they viewed as the right course: the permanent memorialization of cremated remains. Women were actively involved in the association’s efforts. women in canaIn 1979, the Cremation Association of North America elected not only its first female president, but also the first female president in the history of any death care association. Genevieve “Jinger” Zell, widow of CANA’s past president Clifford F. Zell, Jr., took the reins of the association during a time when cremation was experiencing a major transformation. The U.S. cremation rate reached a tipping point of 10% during her presidency. She was one of the most ardent supporters devoted to continuing CANA’s ideals of inurnment and permanent memorialization, staunchly advocating against the processing of cremated remains. After Zell, women continued attain positions of leadership. Mary Helen Tripp was elected president in 1991, followed by Corrine Olvey in 1997, and, most recently, Sheri Stahl in 2015. Today, CANA boasts some of the most forward-thinking women in the profession: Caressa Hughes, Robbie Pape, Elisa Krcilek, and Erin Whitaker are making their mark in the history of cremation by serving as board members, officers, and advisors of the association that is on the cutting edge of all things cremation. CANA’s executive director is Barbara Kemmis. Under her tutelage, the association has gone from being dependent on a management company to being entirely stand-alone and self-sufficient. Kemmis has been instrumental in the reformation of the industry’s original and foremost Crematory Operations Certification Program™ (COCP™). The COCP was reviewed and revised and a whole new catalog of online professional education programs were developed by CANA’s Education Director Jennifer Head. If you read The Cremationist Magazine, what you read is the direct result of the hard work of Sara Corkery, editor of the trade journal. From past to future, women have played, and will always continue to play, a very important role in all movements in our country. In our ever-evolving society, who better to guide cremation and CANA’s future? This post is the first in our series on the history of cremation to get ready for the opening of The History of Cremation exhibition at the National Museum of Funeral History. Learn more about the exhibit and how you can contribute on the museum’s website. Our second post looks at how the treatment of cremated remains influenced memorialization practices and memorialization practices influenced our treatment of cremated remains. Read on!

|

The Cremation Logs Blog

Cremation experts share the latest news, trends, and creative advice for industry professionals. Register or log in to subscribe and stay engaged with all things cremation. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

|